On the morning of September 11, 2001, the New York City skyline changed forever. Nearly three thousand lives were lost, and the world was thrown into chaos that we still haven’t recovered from. On that unseasonably warm fall morning, hundreds responded to the attacks on the World Trade Center. One of those responders was Brian Gestring.

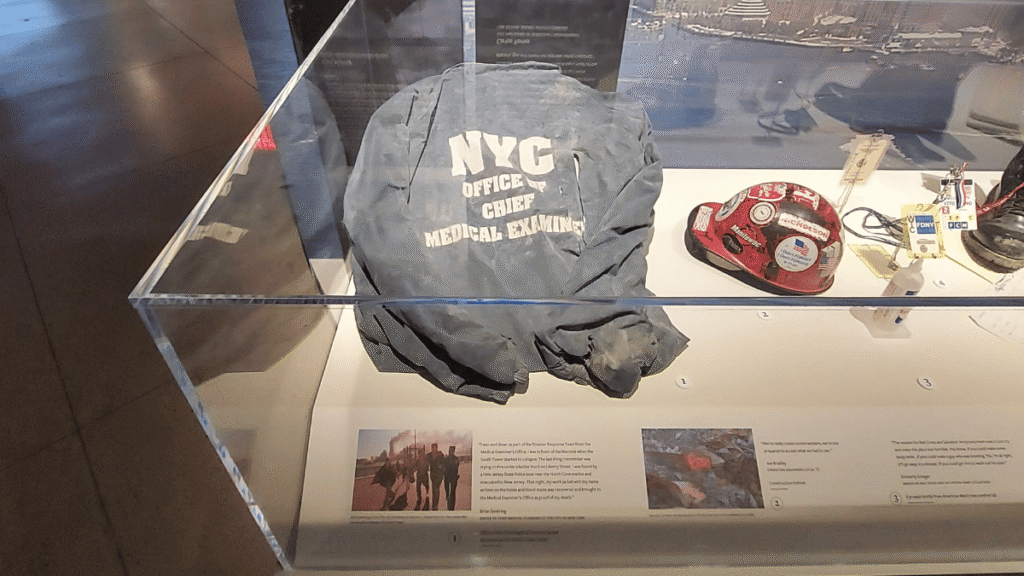

In 2001, Gestring was a supervisor in a crime scene reconstruction unit based out of the Medical Examiner’s Office. He also taught forensic science at Pace University which sat in the shadow of the Twin Towers. When the planes struck the Twin Towers, both of those worlds collided.

Responding down the West Side Highway in a convoy of emergency vehicles, Gestring could see it was going to be bad. Little did he know he would soon find himself under the collapsing South Tower. What happened to him there, and how he has carried it since, reveals not only a story of survival but also the lasting toll such work can take on those who bear witness to tragedy.

The Call to the Towers

That morning started like any other. While Gestring had been out late the night before at a Homicide in the Bronx, now he was sitting in a routine annual training session on chemical safety. His phone began to ring. He silenced the call, but more calls continued to come. The next thing he knew, his team was assembling the gear they would need, and they were on the move.

The scene was like no other. The team parked their vehicle on Liberty Street at the base of the South Tower. Debris was everywhere and continued to fall from the wounded Towers. Unfortunately, that was not all that was falling. People who must have been facing unspeakable horrors decided that falling over 80 floors to their deaths was a better alternative, and jumpers were everywhere. Gestring would never forget the silence before the impact and the sound like a large water balloon when they struck the ground. He remembered making eye contact with some of them. Years later, he would say those moments had never left him.

The Collapse

The location where his team was initially told to set up wasn’t safe, but there was no way to reach anyone via radio. One of the main radio receivers was on the top of the Towers and communications were problematic.

Gestring separated from his team and started walking to the fire command post which was in the base of the North Tower to get a better idea of where their unit should relocate to. As he was walking North Bound in front of the Marriot Hotel, he heard a deep rumbling and the sky went black. It was 9:59 am. The last thing he remembered was sprinting toward a parked FDNY ladder truck, hoping the heavy vehicle could shield him. To this day, he doesn’t know if he made it before he was knocked unconscious.

Pulled from the Rubble

Gestring was found unconscious over a railing on the south side of the North Cove marina. How he got from his last memory to where he was found remains a mystery. He was carried on to a boat and evacuated to Jersey City, NJ. Drifting in and out of consciousness, he later remembered the rumble of an engine, being in a vertical position, and a French blue sleeve next to him.

While Gestring was the most seriously injured person on the boat, everyone was pretty banged up.

As luck would have it, while they had been separated when the South Tower collapsed, Gestring and his team had been evacuated on the same boat and reunited as he was being carried off the boat.

Gestring now struggled to stay conscious as he was being treated by EMS workers. The back of his head was open to the skull; he had glass and metal in his eyes, and had an injury to the top of his right hand with tendons hanging out. And those were just the injuries he knew about at this point.

Gestring remained conscious and was able to tell the ER staff Carol, his wife at the time, name and phone number. Anticipating much worse injuries, the ER staff sent him off to a floor in the hospital where he remained unattended until Carol found him.

His Own Personal Medical Team

Once Carol got the call from the hospital, she called Brian’s brother Craig who was in Illinois at the time. While Carol was picking Brian’s mother up and heading to the hospital, Craig was able to mobilize an impressive medical team. Brian’s other brother Mark is a Trauma Surgeon, and his wife is a Physician’s Assistant. Carol’s friend Lisa Bonin is a Physician’s Assistant and Stephanie Renolds is a nurse. From four states away, Craig reached out to everyone and got them heading to Jersey City Medical Center where Brian had been taken.

Surprisingly, Brian’s bother Mark, who had just driven 350 miles to get there, was the first doctor to treat him. The hospital had assumed that they would be receiving many more victims from the attacks and were all waiting in the Emergency Room. At the time, they didn’t know that you either got out or you didn’t and that they wouldn’t be receiving many no matter how long they waited.

After a split-second assessment, Mark and Holly began working on Brian’s right hand and Lisa and Stephanie began working on closing his head wound. Once Gestring was stable, the hospital reinserted themselves into his care. He had multiple surgeries to remove glass and metal from his eyes, and they monitored his other injuries. For the first several days, his eyes were bandaged shut, then they were coated in an antibacterial gel the consistency of Vaseline.

The First to See, But the Last to Know

In a strange twist, at 9:59 am on September 11th, Gestring was one of the first people in the world to know something happened to the South Tower, but one of the last people in the world to know what.

There was a roar, the sky went black, then he was out. In the hospital his eyes were out of commission. A little over a week later he regained a little of his vision. As he was leaving Jersey City Medical Center heading to Morristown Memorial Hospital, he saw the new skyline and had to come to terms with what was old news to everyone else in the world.

The Long Recovery

Leaving the hospital was only the start. At home, Gestring found that the head injury affected almost everything he tried to do. Tasks that once came easily now took enormous effort. Reading was nearly impossible. The letters swam on the page, and he could not hold a line of thought for long. Even short stretches of concentration left him exhausted.

The setbacks were discouraging. His professional life had always depended on focus and careful attention to detail, and now those skills felt out of reach. Still, he searched for ways to rebuild. One of those ways was to try and understand what had happened to him. He went through every photograph and video he could find to try and understand why he had lived when so many others who stood near him did not.

Through these efforts, he was able to identify the boat that had found him by the North Cove marina and the crew that piloted her that day. He was able to both personally thank them and get them the recognition they deserved for their heroism.

As Gestring continued to heal, he continued searching for any clues of how he had gotten from where he was knocked unconscious to where he was found, but that last ¼ mile proved elusive.

Returning to Work

Even though he wasn’t fully recovered, Gestring was itching to get back to work. As soon as he was able, he started ½ time at first, then gradually extending his day. As luck would have it, his first day back was scheduled for November 12th, the day American Airlines Flight 587 crashed into a residential neighborhood in Queens. Before 9/11, an airplane crash into the city was considered one of the worst-case scenarios. Now it was just Monday. With all the extra resources already in place, the recovery efforts related to Flight 587 were almost seamless.

He also returned to teaching at Pace. If you weren’t there, it was hard to understand, but there was a real need to try and return to normal, whatever normal was. The underground fires were still burning and the smell engulfed lower Manhattan. Pace was right next to ground zero, but it was important for the students that knew Gestring to see him return.

Working at the Office of Chief Medical Examiner where the effort to identify all the victims was ongoing and Pace University, which was feet away from Ground Zero, it was impossible to escape the fallout of that tragic day. But every case he worked, every lecture he taught brought him closer to the life he knew before the world changed forever.

Speaking Out

Brian Gestring has been a fellow of the American Academy of Forensic Science (AAFS) for over two decades. The AAFS recently started a committee to look at how their membership was being affected by the daily traumas they witnessed doing their job and Gestring is a member of that committee. Past President Ken Williams knew of Brian’s experiences on 9/11 and persuaded him to write a piece for the AAFS newsletter on the 23rd anniversary.

Up until this point, Gestring rarely spoke about his experiences. It is uncomfortable and still a little raw. But Ken was right. This was an important step in acknowledging how forensic providers are being affected by their work.

This year, his shell cracked a little further. The recent firings of the staff for the World Trade Center Health Program and the threats to its funding have encouraged Gestring to speak out and share his experiences even more.

Continuing the Work

Survival shaped his life and motivates him even to this day. Gestring coordinated New York State’s Forensic Laboratory Report Standardization Project ensuring that New York’s accredited forensic laboratories all use the same defined terms, have standardized reporting language, and established times when qualifiers are used to ensure that everyone understands the limitations of the report. Under Gestring, New York is the only state that has been able to adopt this critical recommendation from the 2009 National Academies of Sciences report on strengthening forensic science.

He also is the principal architect of New York’s statewide approach to crime laboratory backlog management. Crime lab backlogs have been reported all over the country and at times crippled the criminal justice system. Gestring’s approach is still the only of its kind in the nation and allows all the labs in the state the benefit when one identifies an effective strategy.

Gestring is now a consultant with 4n6services and in addition to his normal work, still presents at national meetings and publishes on ways to improve how forensic science is used in the criminal justice system.

Carrying the Memory

Today, Brian Gestring lives with both the physical and emotional reminders of that morning. His scars mark the danger he survived, and his memories hold the faces of those who did not. The pain never fully left him, but he has turned it into a purpose.

His story is not only about surviving the collapse of the South Tower; it is also about the aftermath. It is also about the years that followed. Forensic scientists like Brian Gestring carry more than physical injuries. They live with the weight of what they have seen, and he has said that burying those memories only makes them heavier.

More than two decades later, September 11 remains with him. It returns in the quiet moments, in the classroom, in the lab, or on a simple walk with his dog. The day is woven into who he is: professor, scientist, father, survivor. None of those roles can be separated from the others, and together they form the life he built after the towers fell.

In 2011, Gestring was asked what he wanted to remember from 9/11 and what he wanted to forget. Obviously, Gestring would want to remember how he got that last ¼ mile from where he was knocked unconscious, but strangely, he did not want to forget anything else. He said “On that same day the world saw great horrors and great acts of heroism. Avoiding one denies the other.”

His Own Cold Case

Brian Gestring has never given up on finding out how he made it out alive. If someone helped him, he is determined to find them and thank them.